A few days ago, a couple of videos by Farmer Leaf were published on the situation of leaves prices in Yunnan, with some insights similar to an article I posted back in late January, written with a slight tone of historical catastrophism, which, rereading it now, almost feels like a premonition. But that happens because history repeats itself in a damnably perpetual way, and I take no credit for that. Now, I don’t think William needs my promotion, I’ve never even spoken to him, to be honest, but I believe he’s one of the people with the most complete, intellectually solid, and sincere vision of the Pu’er landscape, at least on the western side, and, most importantly, capable of combining field experience with analytical clarity, not only because he lives and produces tea in Yunnan. After all, a heart patient is not automatically a great cardiologist, right? For this reason, I would like to ideally connect to what was said in the videos, and perhaps push the boundaries of the discussion a bit further. I know this might seem like an idle exercise, especially now that we’re on the threshold of a season that in many areas hasn’t yet shown itself for what it will be, but I believe the world of tea is already saturated with misleading narratives, or overly bent towards consumption and function-driven logic, so I think many can still tolerate one more.

In some areas like Jingmai, but also in the whole Lincang region, Wuliang, and many parts of Bulang, for example, we have seen a significant depreciation. Not all in the same way, as the price of Yiwu leaves has remained almost unchanged in the famous villages, likewise in Bingdao, although I’ve heard of at least a 10% drop in surrounding villages. The forecast is that plantation and old trees materials from less famous areas, including gushu from some terroirs, will be the most affected. It’s no secret that Pu’er has become almost a superhuman niche game in the last 10-12 years, but was this scenario so unpredictable?

The last discussions on this topic were buried by me in 2014 when more and more people, myself included, became involved with Pu’er, along with a sinking fleet of capital supporters still rushing towards creditors because they considered it a good investment. The growth of the sector was predicted to be unstoppable, which indeed happened for the next ten years. But now it’s no longer like that. The signs have been there for a long time, just like they were present in 2007, although I stand by my previous position, namely that today the situation doesn’t verge on tragedy as it did back then.

What is truly tragic is that Pu’er has reached ridiculously high prices, and in economic terms, this doesn’t mean that people can no longer afford it, which is the point that many emphasize, as if saying that there will always be people willing to spend; the problem lies in the willingness. When the price of a good drastically exceeds its perceived or utilitarian value, cognitive dissonance occurs in consumers, leading to a drop in demand despite the availability of money, simply due to economic rationality. The opportunity cost (what one gives up) becomes too high compared to the perceived benefit. This is in line both with prospect theory, which suggests people react to losses by perceiving an excessive price as “unfair,” and with the luxury paradox. Luxury, which has often been used as a justification for the monstrous figures requested, actually operates in a paradoxical way where some goods lose their appeal if they become too accessible or even too exclusive. A good loses its appeal as a status symbol if its accessibility (real or perceived) collapses.

Price is not just a number; it is a psychological signal, and the breaking point is not universal. Exceptions are represented, for example, by works of art: they maintain high prices for centuries because they embody the brilliance of human genius, something that transcends mere consumption; they do not extinguish or exhaust in the face of the tangible, as they serve no purpose other than themselves. Their value transcends consistency, even while having physical effectiveness; it’s a status that no other thing in the world possesses. But for most goods, including Pu’er, when the price loses all connection to the economic, cultural, or functional reality, the market simply collapses.

I remember that a while ago, people often debated the origins of capitalism, the rise of the West, and how it had overshadowed the Eastern economy in some ways, contributing to a geopolitical gap that is now not so clear. It was in this context that Pomeranz’s “Great Divergence” concept emerged. This was later placed in an economic context by Robert Shiller, who understood it as a situation where financial prices deviate too far from the real economy, creating imbalances destined to correct themselves, often traumatically. The way to identify this phenomenon comes from observing its three main drivers:

– Economic narratives: shared cultural constructions that influence collective economic behavior, often independent of fundamentals. These narratives, such as “the tea from this mountain is liquid gold,” “only here can you find true gushu from 3,000-year-old trees,” “the stock of this Sheng keeps increasing in value,” or “this is the last chance to buy before prices explode,” act as psychological catalysts, amplifying expectations and contributing to speculative communication. The power of a narrative lies in its ability to be replicated and spread, much like a virus.

– Positive feedback loop: a dynamic mechanism where an increase in the price of a financial asset attracts further investment, which in turn drives prices even higher. This process can generate a self-reinforcing spiral disconnected from fundamental values, further fueling the underlying narrative. It’s a recurring dynamic in speculative markets, often a precursor to a correction.

– Imitative behaviors: the tendency of economic actors to replicate others’ decisions rather than base their choices on an independent analysis of available information. This behavior arises from both cognitive (reducing uncertainty) and social (fear of being excluded from collective gain or consumption) incentives, and is one of the main forces amplifying the effects of dominant narratives in markets.

The key point to understand is that no divergence between prices and reality can last forever, none. You might ask, “What about works of art?” Works of art don’t enter into this context because they don’t have divergence. This sets in when the vicious cycle becomes unstable, because goods like tea are always subject to physical constraints, like having a house on the side of a hill in an area that is perpetually at risk of earthquakes. For real goods, final demand always depends on tangible utility, whether it’s for dwelling, consuming, or earning. If this function is lost in products that naturally possess it, the market collapses in the end.

The significant difference from wine is that in the latter, entire areas have seen an increase in land cost and corresponding product beyond imagination, like Pu’er, but there are still labels that are more accessible and others totally out of reach for 90% of people, and both contribute to maintaining the peak of that specific terroir, which remains accessible but sufficiently elitist. In Pu’er, this doesn’t happen, which leads everything to a single standardized dimension. But it isn’t the same for quality. An example can be that all Bingdao shengs are expensive, some more prohibitive than others, but all are excessively costly and generally inaccessible, even the mediocre ones. The quality of raw material can differ even within the same micro-territorial context, but, above all, the hand of the producer is often unknown in the world of Pu’er, reducing everything to a blind purchase if you go outside your small circle of trusted producers or traders. According to this mechanism, if one producer in Montrachet makes a mediocre wine, it’s an isolated case; if someone sprays herbicides every Friday or produces low-level Pu’er in Yi Shan Mo, everyone risks being affected.

Secondly, there is the crisis of trust, which arises when investors realize that the price is an “empty promise” in terms of missed capitalization or, at the same time, in terms of unfulfilled organoleptic quality, no matter how high it may be. Furthermore, the crisis of trust sets in when uncertainty exceeds average tolerance thresholds. Rigged auctions, counterfeits, false claims about the region and age of the trees — all factors contributing to the genesis of distrust. Have you ever seen cakes that looked ordinary, wrapped in plain white paper, always nibbled by the chewing apparatus of some friendly larva, with a damp stain, deliberately present to legitimize a supposed date, affixed a line before a price with 3 or 4 digits? If you were to sell a Chateau d’Yquem, pick any vintage as long as it’s not the 2008, to a wine expert, but that Sauternes were in a naked bottle, without a label, do you think they’d be willing to give you $600 on trust alone? Without clear traceability, strict controls based also on biochemical analysis, do you think people would spend a fortune on any Burgundy wine? In these contexts, people self-report among neighbors, whereas with Pu’er, there still seem to be actors who want that jianghu, that shadow line that seemingly benefits everyone. Wine is clearly different and not all concepts can be applied to tea, as it’s a different raw material. But why is it that everything becomes tolerable for Pu’er?

Finally, there are external interventions, or regulatory agents that trigger corrections, which in this case can be merchants or investors. The money flow stops, and the machine halts, and this is the third reason for the unsustainability of the divergence.

All these factors are usually monitored by financial experts to assess the health of the current market but also to avoid excessive financialization. If a good loses sight of its utility principle, it becomes an asset detached from what makes it itself, turning into a tool for speculation. So, I ask once again: why is there such a desperate effort in Pu’er to gamble and push itself to the edge of this condition?

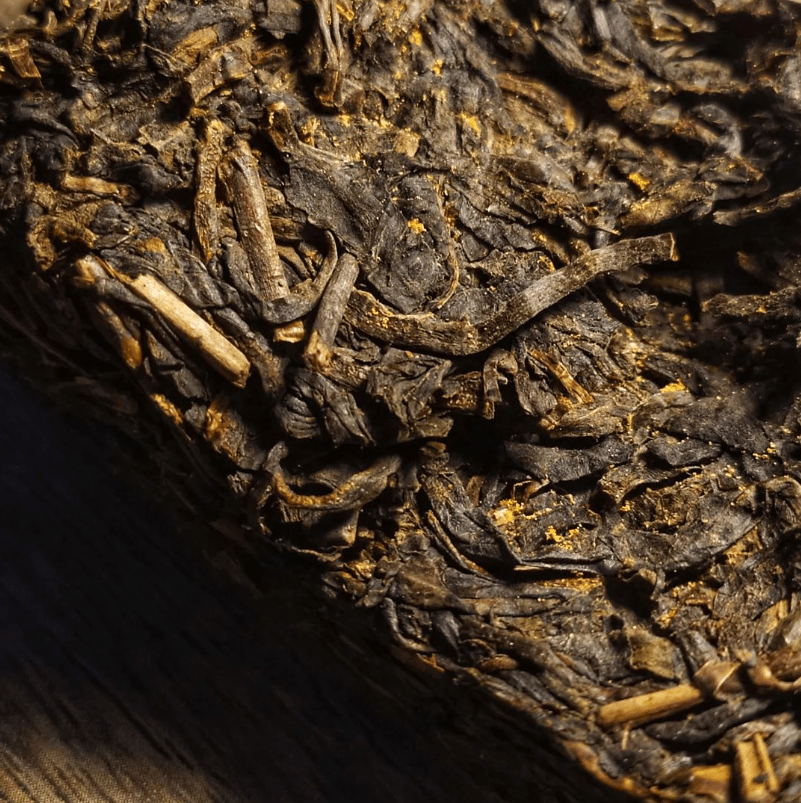

Complicit in all these self-flagellation efforts are surely all those photos, those beautiful live postcards with tea trees standing like soldiers at attention, ready to go to war to satisfy our palates, slaves to a huigan, an authenticity and a cha qi at $2/g findable only there, and I mean only there in those 5 square meters of land immortalized, because only there, according to the seller, God has cast his gaze, good tea is made only at that spot, everything else has obviously been planted to shade that little patch of earth, not to be harvested and sold. What they might not show you is how the person taking the photo might be standing on a guardrail next to the highway, and maybe the grass burnt by pesticides gets cut out with editing, as well as the poorly pruned trees (sometimes they don’t even hide those), or other similar things. Or, simply, the tea doesn’t even come from that patch of earth, because let’s be honest, buying tea is often not just an act of trust, it’s entirely an act of faith. This doesn’t apply to everyone, but it’s a concept that applies to many.

There are no certifications to guarantee the maintenance of a supply chain, nor that a fair price is paid to the producer or farmer, nor control over denominations like in wines. There are chemometric authentication methods through the analysis of stable isotope ratios to trace the origin and harvest year, but I’m smiling just thinking about it. $400 for 357 grams of pure “maybe” seems a bit too much. Half would still be too much. As you can see, the problem is not whether one can afford it or not, for once the problem isn’t money. The problem is the physiological rejection, that immune response of my body against the enormous “if” that resides in my cup, which I’m about to swallow, hoping that the huigan will overwhelm me so I don’t have to engage in psychomanipulative strategies and explain to myself why I spent yet another boatload of money on something that’s barely worth a third of what I paid for it. Usually when there is asymmetry of information between the buyer and the seller, an average price is paid due to the lack of knowledge of one of the two parties. But in Pu’er this does not happen.

And having mentioned authenticity, I’ll refer to the next crazy price-justifying argument. I remember an interesting article by Shuenn-Der Yu, an anthropologist from Academia Sinica in Taipei, who concluded by saying, “Ironically, the story of Puer tea demonstrates that the concern for authenticity may have reached a state where no one cares what Puer really is, so long as the current version of the tradition generates profits.” And here comes another bitter pill to swallow. The campaign for understanding what is authentic in the world of Pu’er has been going on for at least 50 years, and today we are still at the same point, the starting point. Authenticity has moved through the debate between wet and dry storage, between terrace tea and forest tea, until reaching the exasperation of single-origin, which cannot be guaranteed, and the compulsive search for gushu. The search for authenticity has poured into the desire to know the exact location of the bathroom closest to the wok that generated the leaves of that cake from the Banpo forest and the need for those trees to date back to the Qinghai campaign of 1723. Otherwise, you’ll never know what authentic Pu’er tastes like. It’s not a communicative strategy adopted by everyone, but there’s always someone ready to pull out the sign saying “I have the real gushu, the others are fake.”

From the late Qing period, blending (pinpei, 拼配) was considered a refined skill, the result of long training and experience, not unlike, in rigor and sensitivity, the art of blending in whisky or tobacco. This technique continued to represent an essential component of production, both for shenh ad shou Pu’er, continuing its evolution even within large state-owned companies in modern times. But today, authenticity resides in the single village, in the extreme representation of terroir, in tasting the locality, an invitation to the sage of purity and a claim to a place, as happens with French crus or Italian MGA. Too bad that in Pu’er there is nothing similar, neither in historical documentation nor in tradition, nor, again, in the concept of denomination. And without denominations and identity controls, which terroir are we talking about exactly? We can talk about it when we are in that mountain, in that forest, tasting the tea that comes from it because we know who worked it or picked it. But hundreds or thousands of kilometers away, how does that certainty remain intact?

Apart from the controls in some areas, in other parts no one will tell you the truth about what’s happening. Ten years ago, MarshalN wrote, “If you think about it, nothing stops a seller from going to the nearest Chinatown supermarket, buying a bunch of tea cans that cost $5 each, emptying them, repackaging them as quality tea, and reselling them at a 4x markup,” and what has changed in 10 years? Nothing.

The marketing of Pu’er tea has for many years been a choreographed performance, orchestrated through often incomplete contracts that leave excessive room for opportunistic behavior. This modus operandi can be rationalized by observing three harmful symptoms: the sanctification of space, the providential narrative, and the pseudo-religious iconography. All of these are present and exposed above. The Pu’er market has been plundered by what should be the true agronomic meaning and sense of terroir, which deserves true protection, not mere commercialization. What should be the core of authenticity becomes the passive accomplice of an economy of hope.

“It’s normal for people to always want more and earn more; it’s useless to play the morality crusader,” is a typical phrase I hear in debates about situations like these, and it is the natural response many would wield in face of this article. Therefore, I would conclude by reaffirming the reasons that constitute the danger of such a perverse economic cycle.

In the relentless pursuit of higher margins, many areas have converted their crops, with reductions in many cases of more than 40% of the land cultivated for essential foods, increasing vulnerability in case of external imbalances. To expand or maintain production, many farmers have taken out high-interest loans, which, naturally, are also increasing, as the bet was based on a continuously rising price for Pu’er, thus increasing pressure on the credit system and families. Now, if the price of raw tea continues to decline in the coming seasons, these farmers would find themselves in technical default. I read somewhere years ago that rural banks in Yunnan had about 40% of their loan portfolio tied to the Pu’er sector: if producers could no longer repay the loans, there would be a risk of chain insolvencies, similar to a mini subprime mortgage crisis:

Farmers → insolvency → rural banks → credit freeze → collapse of local businesses → slow return to normalcy.

So, the point is not just to lower prices, but to rebuild a network of trust. Continuing the speculative system would not only lead to critical adjustments for honest farmers and intermediaries but also to credit rationing phenomena that would prevent rapid recovery or mere subsistence even after the true outbreak of the crisis. Banks and credit institutions could limit loans to avoid adverse selection risks, like financing risky projects, favoring only the large intermediaries and leaving smaller entities behind. And this is a frequent thing that nobody ever talks about.

Moreover, most of the workforce in rural Yunnan is directly or indirectly involved in the sector: farmers, processors, vendors, tea-related tourism employees. With another market crisis, what transferable skills would hundreds of thousands of potential unemployed people have? Economic restructuring is not possible in the short term to cope with a potential crisis, given the absence of industrial alternatives. To conclude this excessively dramatic view, even with a collapse in the value of Pu’er, rents and mortgages would not fall, since for a good initial period, land and properties would still be valued based on high-return expectations, and families would remain trapped in a stagflation trap (despite some sectoral deflation): high production, high costs, falling income, rising underemployment, and declining consumption. I don’t believe Yunnan is in this situation, despite some sectoral deflation and possible inflationary rigidity of essential goods and fixed costs, nor do I think it will get there soon. But this article is an investigation into various perspectives, so it is necessary to describe even extreme but possible conditions.

Essentially, the Pu’er sector, grown under a model of accumulation and continuous speculative expectations, is now facing its structural limits:

- Inflated prices → distorted rents → inefficient resource allocation.

- Dependency on a single product → systemic vulnerability.

- Lack of diversification and resilience → risk of regional social and economic crisis.

The Pu’er market has evolved into a microcosm of financialized capitalism, where the described drivers create a deadly divergence between price and reality. The correction is painful but necessary, as only by anchoring the price to real values (quality more closely correlated with price, an ethical and certified supply chain, cultural utility) can we avoid the trap of the “Great Divergence.” As Galbraith wrote: “Everyone thinks they can leave the party before the punch bowl runs dry. But the punch always runs dry suddenly.”

In light of the above, the solutions – though complex and not immediately applicable – must include a selective revision of price levels, especially in areas that have experienced the sharpest increases in recent years. This recalibration would help to rise quality, to reduce the entry barriers that currently discourage new operators and consumers in a sector characterized by volatile and often unstable preferences.

It is true that there is a niche of loyal consumers, deeply connected to Pu’er from both a cultural and taste perspective; however, most consumers show high price sensitivity, and in the event of compromised accessibility, they will drastically reduce consumption or migrate towards alternative tea varieties, or turn to other Pu’er production areas such as Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, which are more economically sustainable and are now producing excellent teas.

As also highlighted by William in his videos, another key strategy is diversification: particularly the development of sustainable and integrated tourism (ecotourism) and the reintegration of agricultural crops suited not only for human consumption but also functional for renewable energy production, such as biomass for biogas, or alternative crops like coffee, given the growing prestige of the Menghai region, where extremely high-quality varieties like Gesha are now being successfully grown, representing promising ways to free local communities from the near-exclusive dependence on tea monoculture.

At the same time, the introduction of a mandatory certification system for Pu’er is necessary as a tool to restore market trust and strengthen the perception of the product’s intrinsic value. The cheerful postcards will not be enough sooner or later. In this regard, the use of blockchain technology – to ensure traceability and transparency – together with the formal recognition of local designations of origin, represents an essential step towards a credible and sustainable revaluation of the entire sector.

From a macroeconomic and credit perspective, if the market continues to show rigidity and an absence of adaptive capacity, it will be inevitable to implement extraordinary intervention tools. Among these, it will be crucial to begin systematic monitoring of essential goods prices in the most affected areas, to contain the regressive effects of the crisis on the most vulnerable households. It will be necessary to consider the possibility of activating public debt moratoriums for small producers, as well as, with extreme caution, evaluating the partial conversion of debt into equity instruments. Although this measure would provide immediate financial relief and potentially facilitate access to certification programs and technical support, it carries significant structural risks: among them, the potential for abuses, the excessive commercialization of production logics, and the disproportionate cession of land-use rights in relation to debts that might be overestimated or poorly contracted.

Those who know me or have had the chance to read what I usually write on my profile know how attached I am to Yunnan and China, and they perfectly understand my language, saturated with admiration for an irreducible people. However, I believe that poetic phrasing, lyrical tones, and romantic philosophy are no longer enough. On the contrary, I think a more critical, aware, and participatory approach is needed: a form of shared responsibility toward a market that has proven extremely fragile and that requires more balance and transparency, for the good of all, those who live there and those, like us, who observe, love, and frequent that world.