In recent years I have repeatedly had the pleasure of trying Ba Nuo teas, it is one of the places that perhaps more than others has taught me to free myself from the “aromatic” dimension of tea and to concentrate on the sip, on the tactile sensations, on the physicality of the brew.

Ba Nuo is a village accessible via narrow, dirt roads, you can still see the old houses, some with sheet metal roofs, flanked by other newer and larger ones, the result of overbuilding and the rush to compulsive urbanism that followed the economic growth of the tea villages.

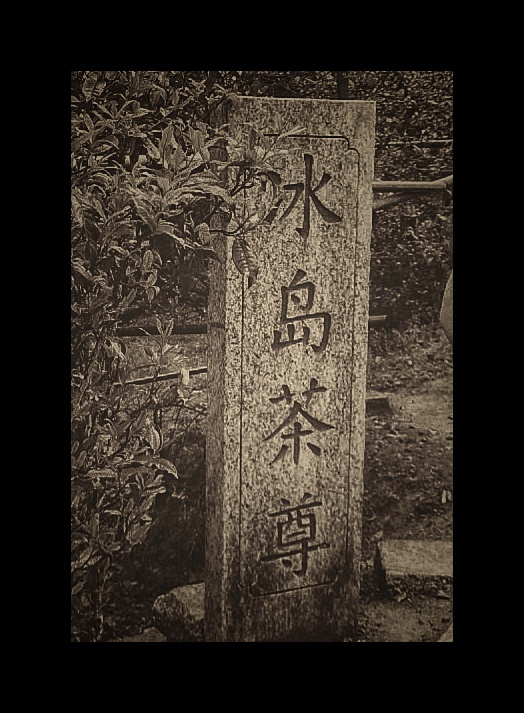

Ba Nuo is located at 1900 meters above sea level, located on the eastern mountain range of Mengku, Dong Ban Shan, populated by around 300 families of the Han and Lahu ethnic groups, practically all of whom work in the tea industry. From the top you can see the villages on the western side, the Xi Ban Shan range, Dong Guo, Xiao Hu Sai, Da Hu Sai, Baka, as if immersed in a Bierstadt painting.

The soils contain a good amount of clay and organic matter, are acidic or sub-acid, with no stones on the surface, but what is striking are the Teng Tiao, also called “vine trees”, which appear like bony and lignified hands dating back to soil, without other plants to counteract them. Pruning the lateral branches favors the apical dominance of the plant, which will develop very elongated branching and leaves placed only on the tips.

Yang, a farmer from Ba Nuo, explained to me how it is not a natural way of cultivation, the land has been prepared, even weeded up to 15 years ago, the surrounding forest has been partly cut down to allow the tea trees to receive more light. Many trees were planted by the Lahu people as early as 300 years ago but the influence of the Han and modernization over time led to the development of this type of cultivation.

Despite the altitude, the agronomic peculiarities, it is not a tea that impresses with its aromas, it is not a complacent palliative for the slaves of fragrance. It took me five months to revisit this tea, perhaps among the most misunderstood in Yunnan, but also one of the most particular.

This Teasenz sheng was harvested in spring 2022 from teng tiao gushu, after being aged 7 months as maocha. I waited 5 months before trying it again, stored at 65% RH, slightly lower than what I store my teas at (68-69% RH).

Timidly the leaves began to advance notes of orchid, dandelion root, wood and toasted cereals. The sip was soft, with aromas of honey, chrysanthemum, apricot, but where it really struck was the qi. It wasn’t a sip that simply came and went, but it came again and again, it continually returned after each infusion and continued even far from the cup, the huigan accentuated the honeyed sweetness even more, surrounded by a light minerality that made the sip every time more pleasant.