Travel 25 kilometers west of Guafengzhai, you will arrive in Mahei. This was the first stage of the ancient tea road on the journey from Laos to China. It is said that one of the original names of Mahei 麻 黑 was “路 边” Lù biān, “Roadside”, because Maheizhai is near the road leading to Laos. In the past, one could start from Laos towards Yiwu and settle the night at the “roadside”, the old Mahei.

Although it is one of the areas that dictates the highest price in Yiwu, only in recent years has there been an incessant attention to the restoration of natural conditions with low interventionism in the tea forests, remedying the tough pruning approach of the 80s-90s in order to increase the yield of ancient trees. Many trees still exceed 300 years but today the mixed and indistinct collection of gushu, young trees and ancient pruned trees is very common and have a clear organoleptic distinction is very complicated. Old trees Mahei pu is much sought after and expensive and its taste embodies part of the soul of Yiwu.

Roughly speaking, it can be said that Mahei tea from ancient wild trees has a softer sip, with a greater opening sweetness and a bitterness that acts as a splendid counterweight. The astringency orchestrates a balanced, lingering and memorable melody, the huigan is intense, powerful and comes quickly, the body is silky and refreshing in which the typical honeyed character is enriched by a complexity unrecoverable in some non-wild or shengtai material.

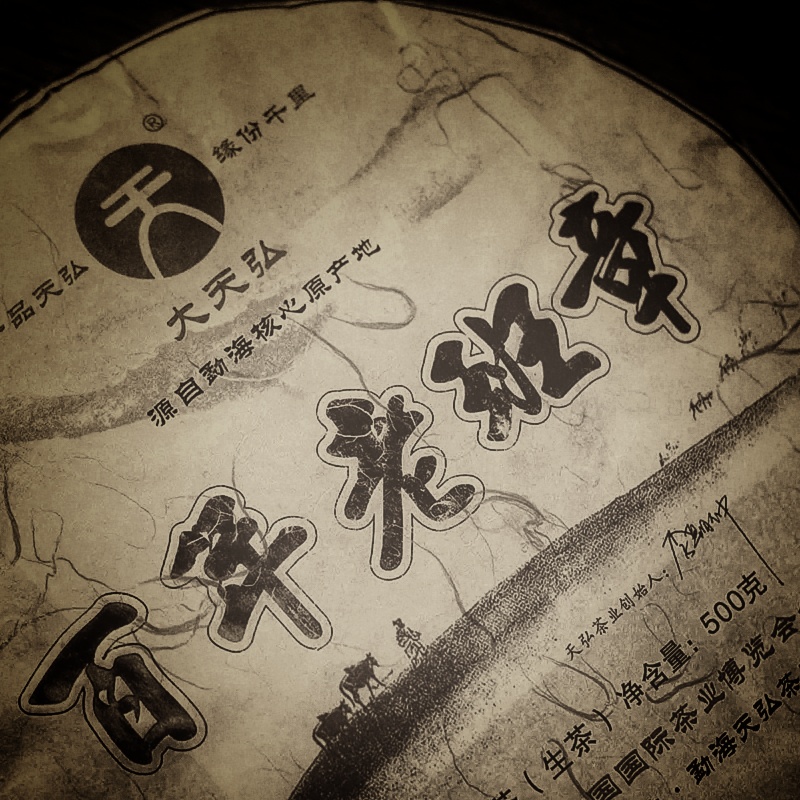

This sheng pu by Thés terre de ciel comes from dashu trees, from material collected in the spring of 2020. In the wet leaves vegetal and wild hints of leather are combined with notes of honey, flowers and caramel, woody fragrances like those of raw mushrooms are the prelude to a sweet opera adorned with a bouquet of aromatic herbs, in which the background smells of petricore and wet vegetation.

The sip has an excellent structure, the pleasant and indulgent bitterness typical of Mahei does not overshadow or obscure the other sensations but instead enhances the tea by contrasting with sweetness and a graceful astringency. The huigan is immediate, minerality makes the mouth water refreshing the palate in which progressively appear aromas of myrtle leaf, dried and candied apple, mango and mulberry. A good roundness accompanied by notes of acacia honey and manuka continue in a very lingering finish at the end of an antithetical taste experience, elegant and wild at the same time, still enlivened by a freshness and a vegetal nuance that herald its evolutionary intent.