Sanmai has gained more and more attention from pu’er enthusiasts in recent years, following the growing interest in the forests of Naka and the Mengsong area.

It is surrounded by some of the most famous mountains in Menghai county, about an hour north of Banpo zhai in the Nannuo area, and an hour and a half south of Huazhuliangzi, reachable passing through the villages of Bameng and Baotang. The forests alternate with the taidicha like an ecological clash between human and nature,the primitive and forest scenarios intensify as you enter the trees towards the North, on the road to Sanmai Laozhai. Once in Sanmai Shangzhai there are only a few kilometers to walk towards the ancient gardens where the natural severity and the inexorability of the woods continues up to the gates of Nanben Laozhai.

Some Mengsong areas seem to open up towards the immense, they consecrate themselves in that “Open” which for Heidegger was the condition in which things, places, people can appear for what they are and not for their numerical value. From the ancient gardens of Sanmai, the valley sloping down to Jinghong, it seems like a mirage that would have elicited a surprised smile, despite his countless trips, even at Frederic Edwin Church.

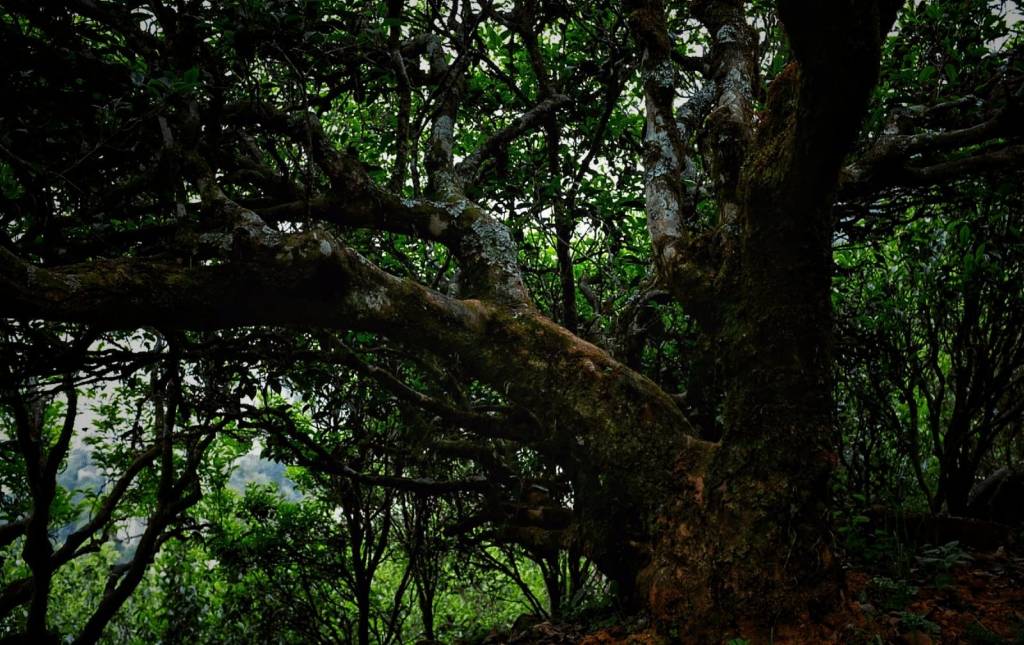

The lichens and saprophytic plants embrace the shrubs in those slopes born from an insane verticalism, which forced the few pickers who bet part of their existence on tea to remain more anchored to the anxieties of concreteness, where the violet of their cheeks was the only chromatic hint among the shades of that primordial greenery.

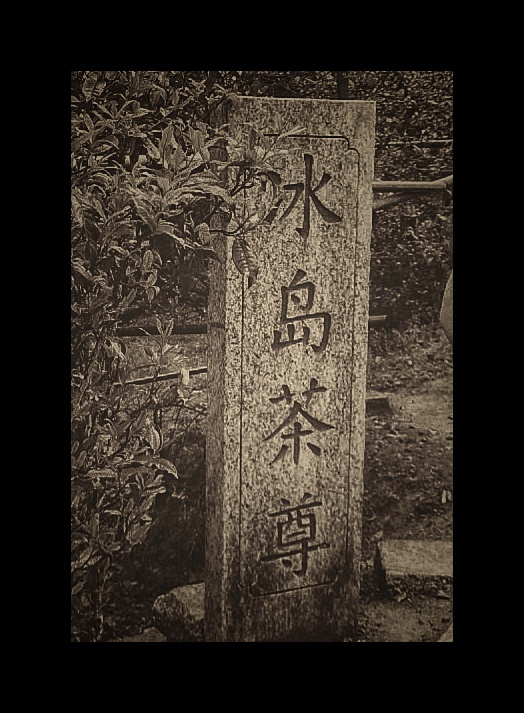

Beyond the narrow and steep road, the rugged gorges and the road surface in which every ravine seems an existential leap, the Hani have found a home for centuries, what was previously a settlement became a security hub in 1934 under the name of Nanben Hebao, for then seeing his own name, Sanmai, only in 1956. Caravans often interrupted their journey here, the rains broke in for days, the oxen slipping caused them to lose the equipment entrusted to them and hence the legend of the name Sanmai, or the place where the tools were tied forming a trellis in the saddle of the ox.

In the ancient gardens tea trees are scattered, some tall yet young seem to converse with the conical bodies of Moso bamboo which often makes this forest look like the ecosystem of Huazhuliangzi.

Here, on the contrary, the bamboo was planted artificially, when tea had not yet reached its current economic importance, as a cash crop for building and textile purposes, and to restore the excessive soil reclamation which led to extremely important erosive phenomena. However, now its removal and reconversion of the land is a problem that inhabitants are facing with difficulty.

The descendants of those exiled souls who bet on the tea of Mengsong and Sanmai now reap the fruit of a legacy that expands beyond its disciplinary limits, to the point of involving the destiny of their own territory.

The rural scenes give value to the time that has passed, the villages develop on the open ridges of the mountains,where the approximately 500 families, mainly Hani, still live mainly thanks to livestock and farming. During the Gatangpa festival you can smell the scent of glutinous rice cakes in the alleys, people walk along the beaten path to reach the place of offerings, and then gather with their families drinking tea and rice wine, even some hens seem busy running out of the old wooden sheds; the black of the ethnic clothes, adorned with silver and silk tassels and the colorful bandanas with geometric motifs offer the only chromatic contrast from the red of the clay soil, as if their smiles were in that instant the only color detail on a black and white background.

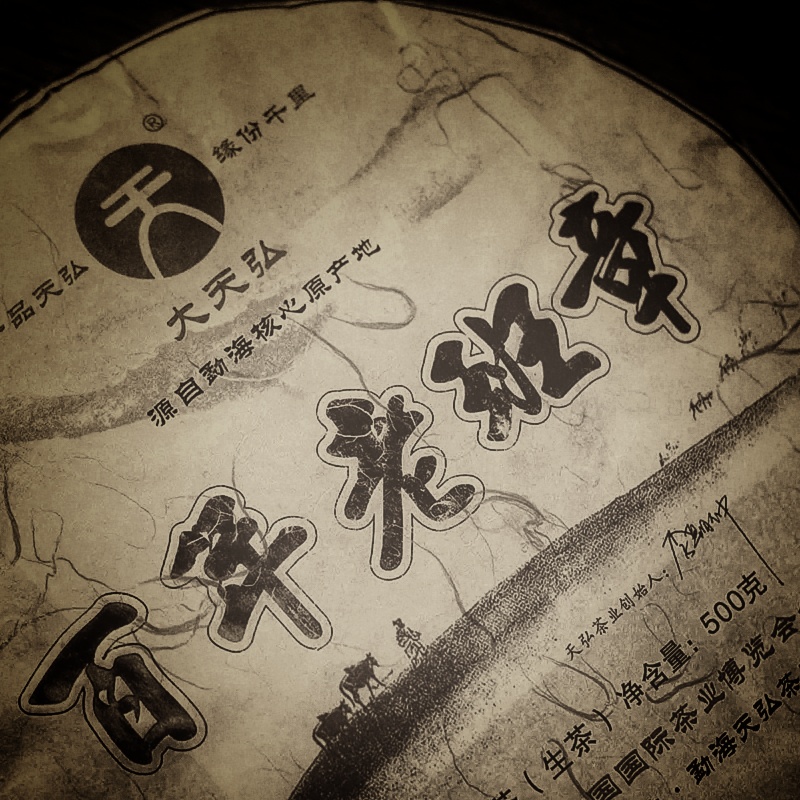

Despite the growing awareness of the value of their tea, it seems that the jianghu forged by conflicts of personality and self-affirmation has not arrived here, their leaves still manage to offer an experience saturated with meaning, freed from economic conflicts and apocryphal slogans; they develop an extended atmosphere in which the link with a past emerges, with those identities, of those perceptions beyond time, which have the ability to bring the aesthetic experience of this village back to the dimension of the present in a different, imperceptible and at the same time sensitive in its liquid revelation.