Politics clouded every public and private space in China at the end of the 70s, revolutionary inspiration raged incessantly from the large squares to the alleys of the rural dimension. The Hunan we know today, a land of extraordinary teas, has seen some of the most important Chinese political figures sit at its hickory wood tables.

The dark liqueur, imbued with smoky aromas, was a participant in the CCP meetings, a witness to history and speeches that were never revealed. The heicha was present during the strategies of a young chairman Mao, of Liu Shaoqi, Wang Zhen, and then-Liberation Army militant Hua Guofeng, who would become the main supporter of the monumental growth of tea cultivation and agricultural modernization during the Cultural Revolution.

Before leaving for Beijing, having defeated the gang led by Mao’s mad widow and being recognized as one of the most powerful men in China until the takeover of the Deng Xiaoping movement, he saw the acreage of Hunan tea increase from 42 to 172 thousand hectares in ten years, even if half were removed around the 90s.

It was the heicha that warmed the souls of the soldiers during the Sino-Japanese battle of Ichigo Operation, that sustained the squadrons on days when not even the land could give relief to the dead.

The huigan of a heicha dates back as the disenchanted voice of those who have now passed away and those who continue their work. Homeland of farmers, idealists, politicians, the look at Hunan is left to a feeling of fatigue and historical awareness that never seems to find rest.

Initially tea was a necessity for the inhabitants of the province, planting it meant having preferential access to coal, kerosene, iron for work tools and fertilizers, furthermore the cooperatives purchased all the tea produced with advances in cash, so that farmers could purchase inputs before harvest, although often at unfair prices.

Even today the roads that lead to Yiyang are part of an arduous pilgrimage where few still venture out, at times it seems like everything has remained still, you seem to have entered another era where in many rural villages no one will offer you a flat image for families or a little speech from a leaflet, rather a cup of tea together and lives to listen to. The people, the territory, are like their teas, a hermitage in the highlands, stranger to that sad modernist compulsion and the sadistic urbanism that seems to bypass history.

In many homes you can still see jars containing remedies and potions on wooden shelves, alongside old ceramic and copper teapots; you are greeted by the warm whine of the kettle on the stove, the wood is now white ash, the smell of smoke still sometimes saturates the atmosphere and the drops of condensation look like tears on the windows, those little things that drag you into your corner of familiar comfort even in the most remote place in the world.

Here, in the early Hongwu years of the Ming Dynasty, Shaanxi tea merchants opened a factory to purchase and process tea, then transport it to Jingyang. After fermentation and flowering was pressed into bricks and then sealed with hemp paper. The central government established inspection and transportation departments in Xining, Hezhou and other places in Shaanxi. Fucha was so important that to prevent tax evasion, sanctions were approved such as beheading for those who illegally left the province with tea and imprisonment or death sentence for officials who allowed their escape.

Anhua tea traders were later empowered to transport tea on grueling and brutal journeys across the Anhua Ancient Tea Horse Road, starting from the ancient market of Huangshaping and Yuzhou, along the Zishui River, then to Dongting Lake by sail boat, and then transferred it to Shaanxi.

However, the birth of the farmer movement and the Shaanxi-Gansu Muslim Uprising blocked tea trade routes in the northwest, resulting in a slowdown in trade and the people of Anhua found themselves without anyone to accept the import, creating a circuit of tax non-compliance that was at that point incurable. Furthermore, foreign capital took advantage of contractual asymmetries and inadequacies between sellers and the Qing government to directly purchase large quantities of cheap tea.

The first signs of recovery came with Zuo Zongtang’s “Tea Law”, opening the doors to a new tributary system and a new and prolific tea export route, but new problems were created, however, during the political disintegration of China under the blows of the warlords of Beiyang and in the early years of the Republic of China.

The central government’s control over local forces weakened considerably, the tea trade in the northwestern region was left to the local government which was solely concerned with the collection of tea taxes without any attention to direct control over tea market policies.

After a slight relief from the markets due to a fiscal relief of the provisional regulation of April 1942, throughout all the 40s to the following 40 years there would no longer be much news; the social unrest, the Sino-Japanese war, the consequent destruction of the roads to block supplies and the lack of intervention in the management of the markets in Hunan caused the disappearance of this type of tea, whose presence persisted almost exclusively at a local level.

The history of Anhua has always concerned people, going beyond politics, beyond market logic, carrying on its shoulders the weight of history and the torment that accompanies the sunset of eras, but it is certain that a new future awaits this territory, worthy of these people and their tea.

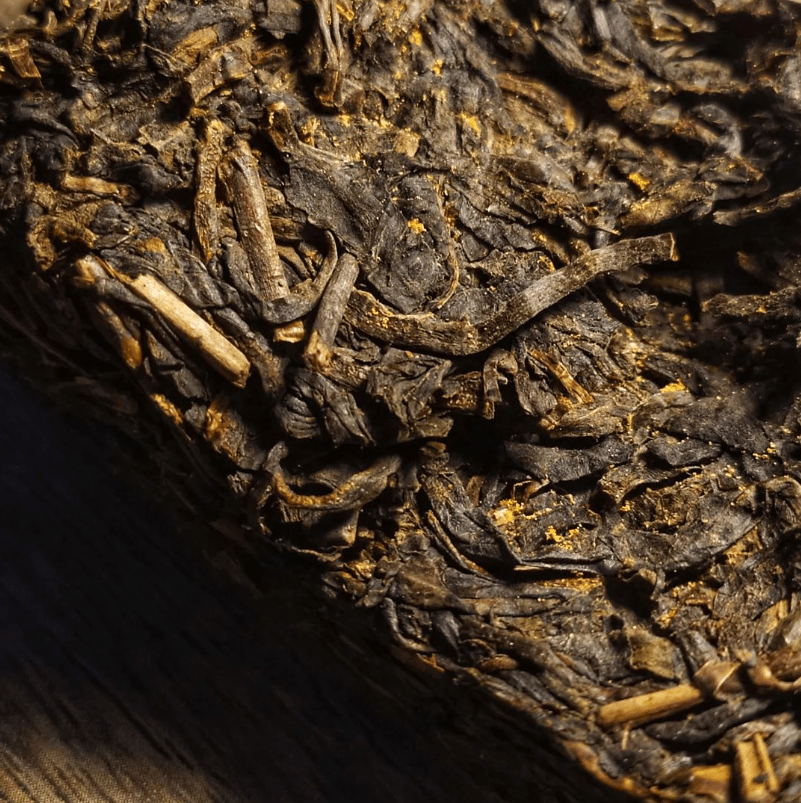

While I’m doing this soliloquy I’m drinking a wonderful Eastern Leaves 2007 Fucha from Anhua, and I am more and more convinced of how this is a tea that more than others is a veteran of incendiary contexts, a reactionary symbol endowed with the cadence of the human voice in narrating with spiritual sincerity our past, when farmers produced tea surrounded by the metallic noise of trucks and the smell of kerosene, fixing the historical truth in the persistence of consciousness.