Universities are fascinating places to discuss how money cannot buy happiness. Perhaps because young people at that age are often strapped for cash and, at the same time, eager to prove that money can’t buy everything, not even that feeling, that harmony between duty and desire, between the passive acceptance of immediate pleasure and the attempt to avoid ephemeral satisfaction. The academies, until one secures a professorship, are also the venues where the idea of the hedonistic treadmill is strongly endorsed. This concept describes the human tendency to incessantly seek pleasures or material improvements without ever achieving lasting satisfaction. Even significant achievements, such as a career advancement, the purchase of a long-desired asset, or a personal milestone, generate an initial peak of satisfaction that nevertheless fades with habituation, returning the individual to their preexisting “set point” or “basal level of happiness.”

I began to wonder, in conversation with colleagues, how one might temporarily yet continuously buy access to the upper floor of happiness, creating an emotional elevator that works on demand, but without the immediate dispersion typical of compulsive buying, and without short-term happiness eventually leading to long-term side effects. Honestly, I was very happy during my early university years, marked by precarious employment and mere subsistence, but I don’t think I’d want to return to those same conditions at this stage of my life. Yet I also don’t want, now that I’m aware of having greater purchasing power, to fall into the collector’s spiral, where happiness is repeatedly renewed and crumbles as one fills a substantial void or into the trap of social comparison, where one measures their value against others in a cultural context that celebrates material success. This phenomenon, as Festinger’s theory of social comparison suggests, has only made many people poorer and poorer. Then, for those of you, like me, who refuse to accept the reality proposed by Lykken and Tellegen, that 50%, and even more, of subjective happiness is hereditary, it becomes necessary to find something that rescues us from our desperate, ill-fated genetic inheritance of perpetual dissatisfaction. I would like to tell you that to govern happiness you must focus not on possession but on mastering your inner judgment; however, I am by no means the most spiritual person you’ll ever meet to be in a position to say that, and besides, I don’t feel like lying to you.

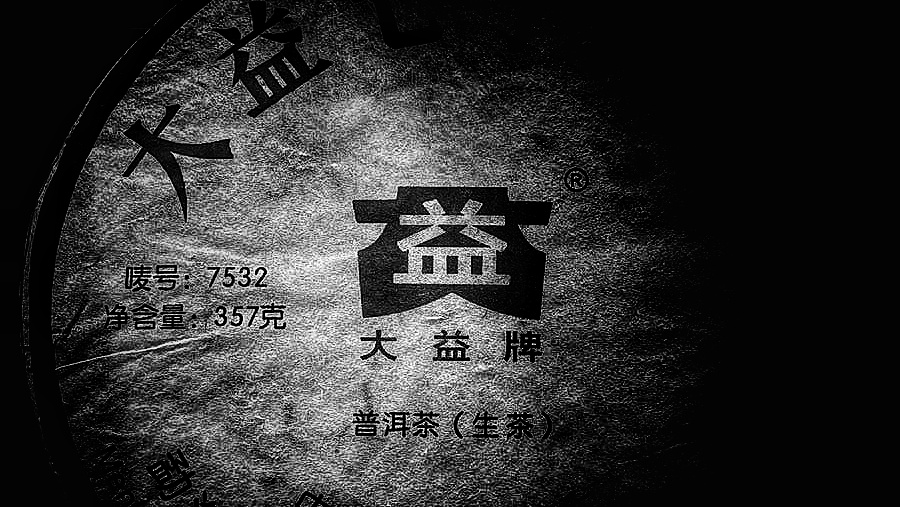

If money cannot buy happiness, we have certainly noticed how it can at least purchase quality, or at the very least, the pretense of quality. I recall several studies, as well as numerous blind tastings, where it consistently emerged that wine, or tea, showed a positive correlation between price and quality, yet the relationship was always incredibly skewed. The most expensive product never ranked first, never. Now, in the Pu’er saga, we see how, as a common snack available everywhere, tea cakes priced at $1–2 per gram appear as if it were normal, as if quality resided only in those teas, and among the buyers of these cakes very few complain about the actual quality of these productions. Beyond the debatable nature of this phenomenon, there are reasons for it.

The first is that these products do indeed embody quality, albeit not to the extent that justifies their exorbitant prices.

The second, as trivial as it may seem, yet as current as a Rolex Submariner on a trust fund kid’s wrist, is that no one is willing to admit to themselves that they’ve burned through a third of their salary on a tea cake that didn’t overwhelm them with a mystical aura but was simply an excellent tea. This is the “sunk cost fallacy”, we recognize that it is irrational to persist in a failing project “because we have invested so much in it,” yet the pain or anger of admitting a loss paralyzes us, doesn’t it? When something is expensive, the link between price and pleasure becomes extremely strong; the price tag transforms into a vehicle for a symbolic narrative that promises a sort of redemption for the expense, an existential revenge. The more you spend, the more you believe you are accessing a “superior” pleasure, rarefied, almost transcendent, and this occurs even before the actual possession of the good, via dopaminergic anticipation.

But the third, and most important, reason is that often the price demands attention. When you spend a lot, it is rare not to notice every smallest detail; every moment can become saturated with meaning. You’re willing to overdose on information just to testify that something is truly extraordinary. This happens even without resorting to selling your organs for a cake, but when you spend a lot, there is no doubt that even someone usually inattentive to every macro-detail would experience the situation differently. In short, both emotional and physical engagement reach their maximum.

Tea in Asia is the apotheosis of agricultural art, and it is natural that people find far more to discuss about a Bi Yun Hao tea cake priced at $500 than about a Xiaguan tuocha costing $10. In the latter case, even if there were something worth discussing, the buyer might subconsciously suppress their thoughts, because it is socially expected that any good priced below a certain threshold has nothing to offer except a “daily squeeze” of repeated consumerism. Many believe that you cannot enter the elite with a ten-dollar purchase, right? But then, how can one leverage this perverse, consumerist vision to one’s advantage without selling both kidneys? Now I come to the point.

What if we viewed price not as a determinant of the intrinsic quality of tea, but as a marker of a sacred boundary between the everyday and the consecrated moment, where money is not betrayed by the real quality (a quality that will never be proportional to the money spent in any case), nor idolized by those who have invested a fortune in what they consider the only way to achieve “true” pleasure? It would no longer be about chasing luxury or a social identity, but about intensifying the present regardless of other factors at play.

To do this, there is no need to spend vast resources; it is enough to pay just a little more than what we consider “normal,” employing a critical yet functional hedonism in which that slight surplus serves as a cognitive bypass and taste criticism functions as a true tool in the search for real quality. Then, all that is needed is to unbox a tea cake and share it, with someone you love or with yourself on a difficult day, thereby consecrating the moment. And you can do this repeatedly, in a logic that transcends every commercial imposition.

That “little bit more” translates into the symbolic gesture of surpassing the ordinary. If you think that isn’t enough, bear in mind that one aspect is the rational awareness of a cognitive bias, and another is overcoming it. It becomes akin to knowing about an optical illusion yet continuing to perceive it even after understanding the trick. Awareness of a bias triggers the analytical system, which is more laborious but corrective; however, it does not interfere with the creation of the bias itself—because biases are effects of evolutionary inertia, developed to survive in a context of cognitive sustainability, not to be right. Essentially, we live in a sort of metacognitive blindness, so why not exploit it.

Let it be clear, this approach would not make extraordinary what is not, nor would it imbue something with an unreal quality it does not possess, but it would help remove many externally induced obstacles to accessing this generative mechanism.

In addition, it would bypass what Byung-Chul Han defines as the “psychopolitics of consumption”, that is the colonization of emotions by the market, which transforms price into an indicator of sentimental intensity, a revealer of truth. Instead, a practice of ritualized happiness is built, as Bruckner would note, whereby a Pu’er tea cake becomes a pragmatic and positive fiction, an accessible simulacrum that does not promise the eternal happiness but guarantees a repeatable fragment of fulfillment.